MANZANAR RINGO-EN MANZANAR RINGO-EN |

See USE NOTICE on Home Page. |

United States Library of Congress Photo courtesy Manzanar Cooperative Enterprises |

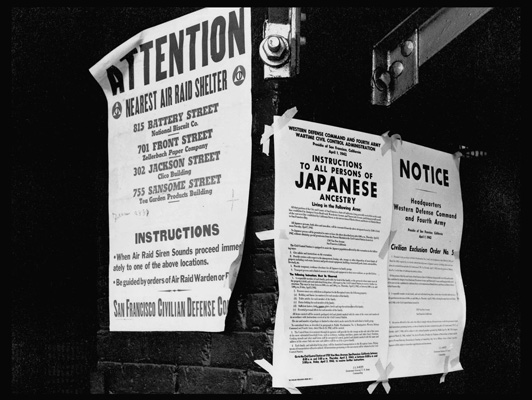

The Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry During WWII By the U.S. War Relocation Authority |

Copies of these pictures can be obtained directly from the National Archives. These images are some of my favorite. There nearly 500 Manzanar internment images in the National Archives files. I encourage you to visit the archives and peruse the many photographs. Once you click on the icon above and are taken to the archives, type in "Manzanar" and then press "Display Results" and the images will be displayed in sets of nine. You might observe, as I did, that the internees appear rather unnaturally joyous in these pictures. I don't think that having been dislocated from their homes and businesses, forced to live in a harsh desert environment and confined to barracks with no insulation would have made them this happy. But as Jeanne Wakatsuki points out in her book, Farewell to Manzanar, Japanese Americans told each other very quietly to "Shikata ga nai" ("It must be done", or, as my Japanese friend says, "Suck it up [and get on with life]." Perhaps this is what encouraged them to put a smile on their face. Text excerpts followed by a "JWH" are from Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston & James D. Houston's book "Farewell to Manzanar" |

Concentration Camp / Internment Camp / Relocation Center? |

| Describing Manzanar and the others as "concentration camps"

conjures horrible images of the ovens of Dachau under the Nazis,

or the Soviet Gulag in Siberia. As bad as they were, the American

concentration camps never approached the horrifying conditions

of the camps in Europe. There were no gas chambers or medical

"experiments" at Manzanar or the other American camps.

There were no attempts to work prisoners to death. In fact, the food and the medical care at Manzanar were better than adequate, in large measure because the Nisei were given the opportunity to provide for themselves. There was one other difference separating the American concentration camps from the European camps. In most instances, families were kept together. The Nisei prized the institution of the family. It may be this difference, more than all others that allowed them to survive and prosper under very difficult circumstances. |

This is a MUST WATCH Video |

|

By Tom Russell (Sung by Tom Paxton)

I am a proud American. I came here in '27, From my homeland of Japan. And I picked your grapes and oranges, Saved some money, bought a store. Until 1942, Pearl Harbor, and the War.

They took our house, the store, the car, And they drove us through the desert, To a place called Manzanar. A Spanish word for apple orchards, Though we saw no apple trees. Just the rows of prison barracks, With the barbed wire boundaries.

Waving free beneath the stars, Till we wake up in the desert, The prisoners of Manzanar, Manzanar.

And now I am an old man. But I don't regret the day That I came here from Japan. But on moonless winter nights, I often wish upon a star, That I'd forget the shame and sorrow, That I felt at Manzanar.

|

|

.

Barracks Construction - 1942

|

|

Overview of the War Relocation Authority Center layout |

|

The Barracks - Tar

Paper and Boards |

| The

barracks at Manzanar were constructed of quarter-inch boards

over a wooden frame, the outsides of which were covered with

tar paper nailed to the roof and walls with batten boards. Heat

was provided by oil-burning furnaces. This was the cheapest,

quickest way to provide living quarters slightly better than

tents. At Manzanar, the cost of this construction was $3,507,018,

or $376 per inmate. According to army regulations, this type of housing was suitable only for combat-trained soldiers, and then only on a temporary basis. The army called this "theater of operations" housing. But at Manzanar and the other camps, these barracks were used as long-term housing for men, women, and children -- who stayed in them for up to three and a half years. In many ways, Questions and answers for Evacuees glossed over, in soothing bureaucratic language, the ramifications of the Nisei's evacuation and the circumstances they would encounter in the camps. The booklet was fairly accurate, however, when it warned the Nisei to be prepared for temperatures varying from "freezing in winter to 115 degrees in...the summer." Manzanar provided both of those extremes, plus wind that whipped the snow across the desert in the winter, and dust in the spring, summer, and fall. Among all the camps, the extremes of temperatures endured by the Nisei ranged from 130 degrees in Poston, Arizona, to minus thirty degrees in Heart Mountain, Wyoming. |

(excerpts from Farewell to Manzanar) The Barracks "Each barracks was divided into six units, sixteen by twenty feet, about the size of a living room, with one bare bulb hanging from the ceiling and an oil stove for heat. We were assigned two of these for the twelve people in our family group; and our official family 'number' was enlarged by three digits - 16 plus the number of this barracks. We were issued steel army cots, two brown army blankets each, and some mattress covers, which my brothers stuffed with straw. The people who had it hardest during the first few months were young couples, many of whom had married just before the evacuation began, in order not to be separated and sent to different camps. Our two rooms were crowded, but at least it was all in the family. My oldest sister and her husband were shoved into one o those sixteen-by-twenty-foot compartments with six people they had never seen before - two other couples, one recently married like themselves, the other with two teenage boys. Partitioning off a room like that wasn't easy. It was bitter cold when we arrived, and the wind did not abate. All they had to use for room dividers were those army blankets, two of which were barely enough to keep one person warm. They argued over whose blanket should be sacrificed and later argued about noise at night - the parents wanted their boys asleep by 9:00 p.m. - and they continued arguing over matters like that for six months, until my sister and her husband left to harvest sugar beets in Idaho. It was grueling work up there, and wages were pitiful, but when the call came through camp for workers to alleviate the wartime labor shortage, it sounded better than their life at Manzanar. They knew they'd have, if nothing else, a room, perhaps a cabin of their own." (JWH) |

Who were the people brought to Manzanar at gunpoint? They shared only one common characteristic: "a Japanese ancestor in any degree." Two-thirds were first-generation American citizens. They lived in American cities, attended American schools, and thought of themselves as Americans. That belief was sorely tested when, by order of President Roosevelt -- an order carried out by General John L. DeWitt, West Coast Commander, and his subordinates -- they were removed from their homes, schools, and businesses, and brought to Manzanar and nine other camps like it. The first-generation Japanese Americans were called, in Japanese, Nisei. A few were second-generation Americans, called Sansei. Neither they nor their parents had ever known any other life than their life in the United States. Almost a third of the prisoners were Japanese citizens, resident aliens by definition of the U.S. immigration law. They were called Issei. All of this group had lived in the United States at least eighteen years, since American borders were closed to Japanese immigrants in 1924. All had been specifically barred from applying for American citizenship. The right to become an American citizen was not allowed to the Japanese until 1952, when quotas were introduced. Because the Issei would have become American citizens, given the opportunity, the Issei and the Sansei are sometimes described generically as Nikkei. |

The numbers alone tell an important part of the internment story. Only 1,875 Nisei from Hawaii, each individually identified as a possible threat to the security of the United States, were interned. The rest of the 120,000 prisoners were from the mainland. Manzanar was the first of ten camps to open. The following list identifies all the camps, their first and last days of operation, and the maximum number of prisoners held at any time in each - and offers a stark picture of the Nisei's fate:

|

Completed Barracks

(excerpts from Farewell to Manzanar) "In Spanish, Manzanar means 'apple orchard.' Great stretches of Owens Valley were once green with orchards and alfalfa fields. It has been a desert ever since its water started flowing south into Los Angeles, sometime during the twenties. But a few rows of untended pear and apple trees were still growing there when the camp opened, where a shallow water table had kept them alive. In the spring of 1943 we moved to Block 28, right up next to one of the old pear orchards. That's where we stayed until the end of the war, and those trees stand in my memory for the turning of our life in camp, from the outrageous to the tolerable." (JWH) "It seems so comical, looking back; we were a band of Charlie Chaplin's marooned in the California desert. But at the time, it was pure chaos. That's the only way to describe it. The evacuation had been so hurriedly planned, the camps so hastily thrown together, nothing was completed when we got there, and almost nothing worked. The kitchens were too small and badly ventilated. Food would spoil from being left out too long. That summer [1941], when the heat got fierce, it would spoil faster. The refrigeration kept breaking down. The cooks, in many cases, had never cooked before The first chef in our block had been a gardener all his life and suddenly found himself preparing three meals a day for 250 people. 'The Manzanar runs' became a condition of life, and you only hoped that when you rushed to the latrine, one would be in working order." (JWH) "Inside it [the latrine] was like all the other latrines. Each block was built to the same design, just as each of the ten camps, from California to Arkansas, was built to a common master plan. It was an open room, over a concrete slab. The sink was a long metal trough against one wall, with a row of spigots for hot and cold water. Down the center of the room twelve toilet bowls were arranged in six pairs, back to back, with no partitions. My mother was a very modest person, and this was going to be agony for her, sitting down in public, among strangers. Like so many of the women there, Mama never did get used to the latrines. It was a humiliation she just learned to endure: shikata ga nai, this cannot b helped. She would quickly subordinate her own desires to those of the family or the community, because she knew cooperation was the only way to survive. At the same time she placed a high premium on personal privacy, respected it in others and insisted upon it for herself. Almost everyone at Manzanar had inherited this pair of traits from the generations before them who had learned to live in a small, crowded country like Japan. Because of the first they were able to take a desolate stretch of wasteland and gradually make it livable. But the entire situation there, especially in the beginning - the packed sleeping quarters, the communal mess halls, the open toilets - all this was an open insult to that other, private self, a slap in the face you were powerless to challenge" (JWH) |

(excerpts from Farewell to Manzanar)

The name Manzanar meant nothing to us when we left Boyle Heights. We didn't know where it was or what it was. We went because the government ordered us to. And, in the case of my older brothers and sisters, we went with a certain amount of relief. They had all heard stories of Japanese homes being attached, of beatings in the streets of California towns. They were as frightened of the Caucasians as Caucasians were of us. Moving, under what appeared to be government protection, to an area less directly threatened by the war seemed not such a bad idea at all. For some it actually sounded like a fine adventure." (JWH) "I had never been outside Los Angeles County, never traveled more than ten miles from the coast, had never even ridden on a bus. I was full of excitement, the way any kid would be, and wanted to look out the window. But for the first few hours the shades were drawn. Around me other people played cards, read magazines, dozed, waiting. I settled back, waiting too, and finally fell asleep. The bus felt very secure to me. Almost half its passengers were immediate relatives. Mama and my older brothers had succeeded in keeping most of us together, on the same bus, headed for the same camp. I didn't realize until much later what a job that was. The strategy had been, first,to have everyone living in the same district when the evacuation began, and then to get all of us included under the same family number, even though names had been changed by marriage. Many families weren't as luck as ours ad suffered months of anguish while trying to arrange transfers from one camp to another." (JWH) "We woke up early, shivering and coated with dust that had blown up through the knotholes and in through the slits around the doorway. During the night Mama had unpacked all our clothes and heaped them on our beds for warmth. Now our cubicle looked as if a great laundry bag had exploded and then been sprayed with fine dust. A skin of sand covered the floor. " (JWH) "My days spent in classrooms are largely a blur now, as one merges into another. What I see clearly is the face of my fourth-grade teacher - a pleasant face, but completely invulnerable, it seemed to me at the time, with sharp, commanding eyes. She came from Kentucky. She wore wedgies, loose slacks, and sweaters that were too short in the sleeves. A tall, heavyset spinster, about forty years old, she always wore a scarf on her head, tied beneath the chin, even during class, and she spoke with a slow, careful Appalachian accent. She was probably the best teacher I've ever had - strict, fair-minded, dedicated to her job. Because of her, when we finally returned to the outside world I was, academically at least, more than prepared to keep up with my peers" (JWH) A

young woman came in, a friend of Chizu's, who lived across the

way. She had studied in Japan for several years. About the time

I went to bed she and Papa began to sing songs in Japanese, warming

their hands on either side of the stove, facing each other in

its glow. After a while Papa sang the first line of the Japanese

national anthem, Kimi ga yo. Woody, Chizu, and Mama knew

the tune, so they hummed along while Papa and the other woman

sang the words. It can be a hearty or a plaintive tune, depending

on your mood. From Papa, that night, it was a deep-throated lament.

Almost invisible in the stove's small glow, tears began running

down his face.

yachiyoni sa-za-re i-shi no i-wa-o to na-ri-te ko-ke no musu made. May thy peaceful reign last long. May it last for thousands of years, Until this tiny stone will grow Into a massive rock, and the moss Will cover it deep and thick" (JWH) |

Destination - Manzanar War Relocation Authority Center

(excerpts from Farewell to Manzanar) For all the pain it caused, the loyalty oath finally did speed up the relocation program. One result was a gradual easing of the congestion in the barracks. In Block 28 we doubled our living space - four rooms for the twelve of us. Ray and Woody walled them with sheetrock. We had ceilings this time, and linoleum floors of solid maroon. You had three colors to choose from - maroon, black, and forest green - and there was plenty of it around by this time. Some families would vie with on another for the most elegant floor designs, obtaining a roll of each color from the supply shed, cutting it into diamonds, squares, or triangles, shining it with heating oil, then leaving their doors open so that passers-by could admire the handiwork." (JWH) [Papa] painted watercolors. Until this time I had not known he could paint. He loved to sketch the mountains. If anything made that country habitable it was the mountains themselves, purple when the sun dropped and so sharply etched in the morning light the granite dazzled almost more than the bright snow lacing it. The nearest peaks rose ten thousand feet higher than the valley floor, with Whitney, the highest, just off to the south. They were important for all of us, but especially for the Issei. Whitney reminded Papa of Fujiyama, that is, it gave him the same kind of spiritual sustenance. The tremendous beauty of those peaks was inspirational, as so many natural forms are to the Japanese (the rocks outside our doorway could be those mountains in miniature). They also represented those forces in nature, those powerful and inevitable forces that cannot be resisted, reminding a man that sometimes he must simply endure that which cannot be changed." (JWH) As the months at Manzanar turned to years, it became a world unto itself, with its own logic and familiar ways. In time, staying there seemed far simpler than moving once again to another, unknown place. It was as if the war were forgotten, our reason for being there forgotten. The fact that America had accused us, or excluded us, or imprisoned us, or whatever it might be called, did not change the kind of world we wanted. Most of us were born in this country; we had no other models. Those parks and gardens lent it an oriental character, but in most ways it was a totally equipped American small town, complete with schools, churches, Boy Scouts, beauty parlors, neighborhood gossip, fire and police departments, glee clubs, softball leagues, Abbott and Costello movies, tennis courts, and traveling shows. (I still remember an Indian who turned up one Saturday billing himself as a Sioux chief, wearing bear claws and head feathers. In the firebreak he sang songs and danced his tribal dances while hundreds of us watched.)" (JWH) |

My sister Lillian was in high school and singing with a hillbilly band called 'The Sierra Stars' - jeans, cowboy hats, two guitars, and a tub bass. And my oldest brother, Bill, led a dance band called 'The Jive Bombers' - brass and rhythm, with cardboard fold-out music stands lettered J.B. Dances were held every weekend in one of the recreational halls. Bill played trumpet and took vocals on Glenn Miller arrangements of such tunes as In the Mood, String of Pearls, and Don't Fence Me In. He didn't sing Don't Fence Me In out of protest, as if trying quietly to mock the authorities. It just happened to be a hit song one year, and they all wanted to be an up-to-date American swing band. They would blast it out into recreation barracks full of bobby-soxed, jitter-bugging couples: Oh, give me land, lots of land Under starry skies above, Don't fence me in. Let me ride through the wide Open country that I love.... Pictures of the band, in their bow ties and jackets, appeared in the high school yearbook for 1943-1944, along with pictures of just about everything else in camp that year. It was called Our World." (JWH) |

JoAnne Keiko

Masuoka Serran of Union City, California writes. |

| Ray, My parents were interned at Manzanar. Edward Fumio Masuoka and Ruth Fujiko Murata Masuoka. They met in San Francisco after being released from camp. Both are deceased now. Unfortunately, they spoke very little about their life at Manzanar. After reading an excerpt of "Farewell to Manzanar" it perked my interest and now I wish I knew more about their life in camp. What little they did tell me was not the same as what I read in the excerpt. I realize that I read a small portion of the story; however, I will read as many stories as I can about camp life. JoAnne Keiko Masuoka Serran (Sansei) - October 2002. |

Dorothea Lange Photos |

|

|

Sierra Crossing | |

|

Ghosts of the Past - Owens Valley Aqueduct & Cottonwood Sawmill | |

|

20 Mule Team History | |

More WW2 War Relocation Authority Center History |

|

|

Manzanar High School |

|

|

Manzanar Journal - Berry Tamura |

|

|

Manzanar Free Press |

|

Sign Guestbook View Old Guest Book Entries Oct 1999 - Feb 2015 (MS Word) |

CONTACT the Pigmy Packer |

View Guestbook View Old Guest Book Entries Oct 1999 - Feb 2015 (PDF) |