MANZANAR RINGO-EN MANZANAR RINGO-EN

|

See USE NOTICE on Home Page. |

|

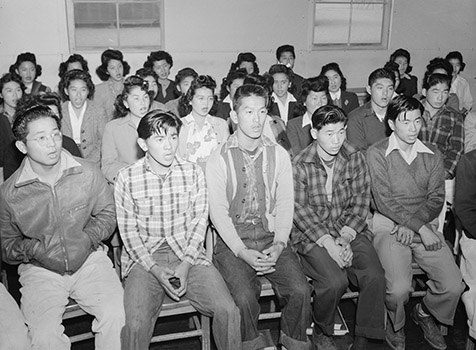

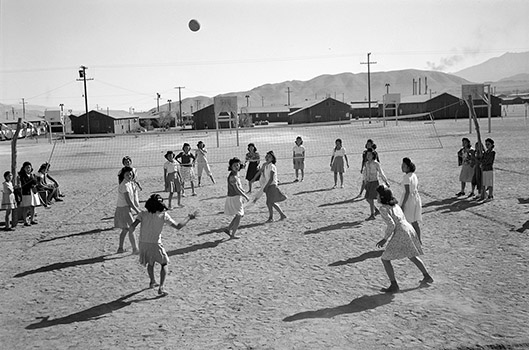

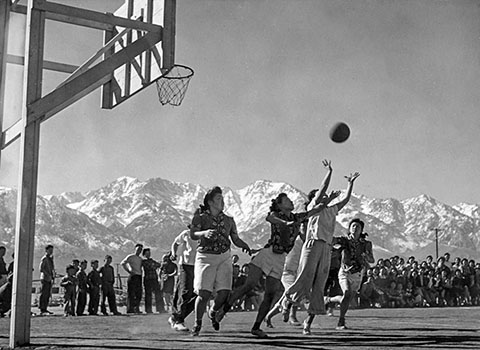

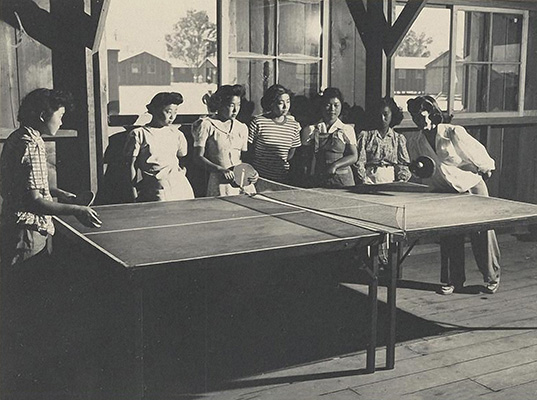

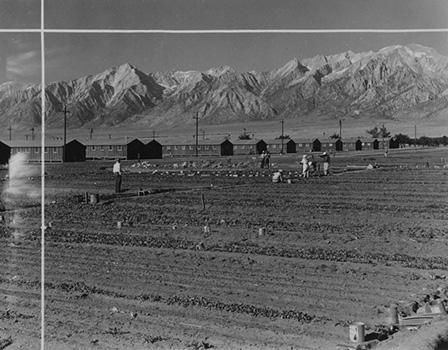

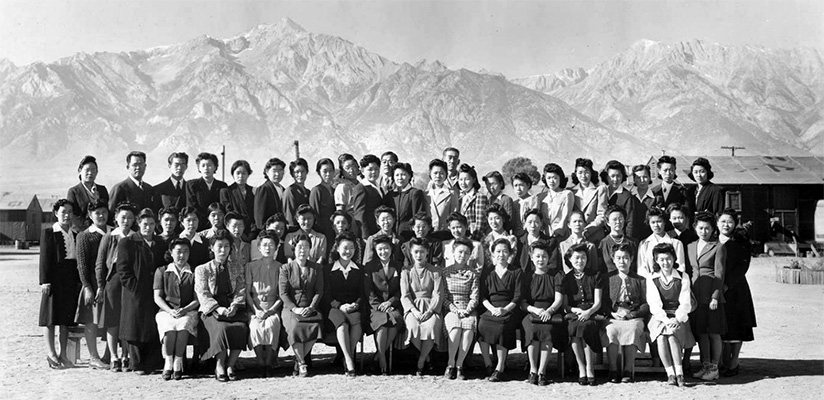

These images are some of my favorite. There nearly 500 Manzanar internment images in the National Archives files. I encourage you to visit the archives and peruse the many photographs. Once you click on the icon above and are taken to the archives, type in "Manzanar" and then press "Display Results" and the images will be displayed in sets of nine. You might observe, as I did, that the internees appear rather unnaturally joyous in these pictures. I don't think that having been dislocated from their homes and businesses, forced to live in a harsh desert environment and confined to barracks with no insulation would have made them this happy. But as Jeanne Wakatsuki points out in her book, Farewell to Manzanar, Japanese Americans told each other very quietly to "Shikata ga nai" ("It must be done", or, as my Japanese friend says, "Suck it up [and get on with life]." Perhaps this is what encouraged them to put a smile on their face. Unless otherwise noted all photographs are from Dorothea Lange. Text excerpts followed by a "JWH" are from Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston & James D. Houston's book "Farewell to Manzanar" |

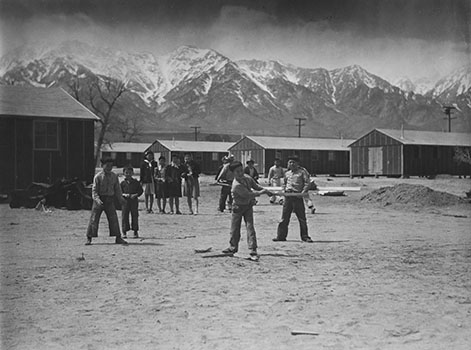

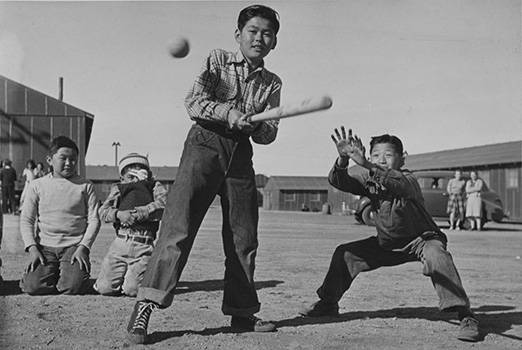

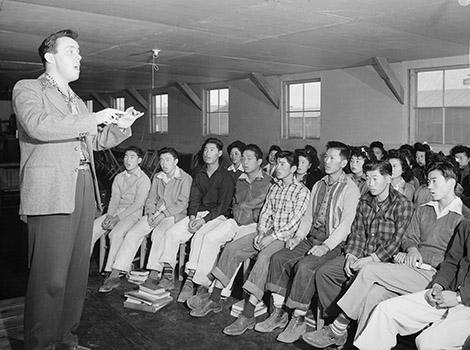

Sports & Other Extra-Curricular Activities

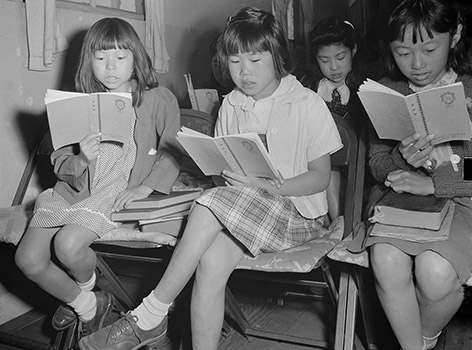

(excerpts from Farewell to Manzanar) "In June the schools were closed for good. After a final commencement exercise the teachers were dismissed. The high school produced a second yearbook, Valediction 1945, summing up its years in camp. The introduction shows a page-wide photo of a forearm and hand squeezing pliers around a length of taut barbed wire strung beneath one of the towers. Across the page runs the caption, 'From Our World . . . through these portals . . . to new horizons.'" (JWH) "Then the word went out that the entire camp would close without fail by December 1 [1945]. Those who did not choose to leave voluntarily would be scheduled for resettlement in weekly quotas. Once you were scheduled, you could choose a place - a state, a city, a town - and the government would pay your way there. If you didn't choose, they'd send you back to the community you lived in before you were evacuated. Papa gave himself up to the schedule. The government had put him here, he reasoned, the government could arrange his departure. What could he lose by waiting? Outside he had no job to go back to. A California law passed in 1943 made it illegal now for Issei to hold commercial fishing licenses. And his boats and nets were gone, he knew - confiscated or stolen. Here in camp he had shelter. The women and children still with him had enough to eat. He decided to sit it out as long as he could." (JWH) "Papa read the papers and studied the changeless peaks, while all around us other families were moving out, forcing our name ever higher on the list. Every day bus loads left from the main gate, heading south with their quotas, filled with Mamas and Papas and Grannies who had postponed movement as long as possible, and soldiers' wives like Chizu, and children like Kiyo and May and me, too young yet to be out on our own. Some of the older folks resisted leaving right up to the end and had to have their bags packed for them and be physically lifted and shoved onto the busses. When our day finally arrived, in early October, there were maybe 2,000 people still living out there, waiting their turn and hoping it wouldn't come." (JWH) "Before the war he [Papa] had always preferred off-beat, unpredictable cars that no one else of his acquaintance would be likely to own. For a couple of years he drove a long, six-cylinder Chrysler that got about nine miles to the gallon. In the early thirties he drove a Terraplane. Late that afternoon he came back from Lone Pine in a midnight blue Nash sedan, fondling the short, stubby gearshift that projected from its dashboard. The gearshift was what attracted him, and it was one of the few parts of that car to reach southern California unscathed. To get all nine of us, plus our clothes and the odds and ends of furniture we'd accumulated, from Owens Valley 225 miles south to Long Beach, Papa had to make the trip three times. He pushed the car so hard it broke down about every hundred miles or so. In all it took four days. ...[Papa's] mood began to match what mine had been since we drove out the main gate, as if what we had all been dreading so long was finally to appear, at any moment, without warning - a burst of machine-gun fire, or a row of Burma-Shave signs saying Japs Go Back Where You Came From. Due to wartime priorities, very little new housing had been developed. Now, 60,000 Japanese Americans were returning to their former communities on the west coast and being put into trailer camps, Quonset huts, back rooms of private homes, church social halls, anywhere they could fit." (JWH) "Mama picked up the kitchenware and some silver she had stored with neighbors in Boyle Heights. But the warehouse where she'd stored the rest had been unaccountable 'robbed' - of furniture, appliances, and most of those silvery anniversary gifts. Papa already knew the car he'd put money on before Pearl Harbor had been repossessed. And, as he suspected, no record of his fishing boats remained. This put him right back where he'd been in 1904, arriving in a new land and starting over from economic zero. Papa would never accept anything like a cannery job. And if he did, Mama's shame would be even greater than his: this would be a sure sign that we had hit rock bottom. So she went to work with as much pride as she could muster. Early each morning she would make up her face. She would fix her hair, cover it with a flimsy net, put on a clean white cannery worker's dress, and stick a brightly colored handkerchief in the lapel pocket. The car pool horn would honk, and she would rush out to join four other Japanese women who had fixed their hair that morning, applied the vanishing cream, and sported freshly ironed hankies." (JWH) "At its peak, in the summer of '42, Manzanar was the biggest city between Reno and Los Angeles, a special kind of western boom town that sprang from the sand, flourished, had its day, and now has all but disappeared. The barracks are gone, torn down right after the war. The guard towers are gone, and the mess halls and shower rooms, the hospital, the tea gardens, and the white buildings outside the compound. Thirty years earlier, army bulldozers had scraped everything clean to start construction." (JWH) |

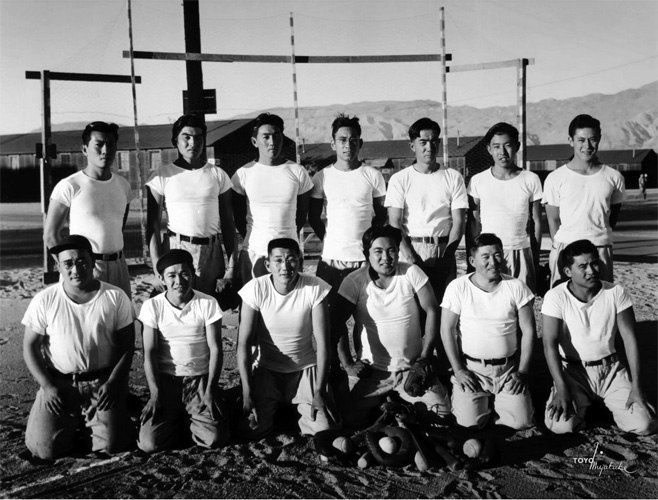

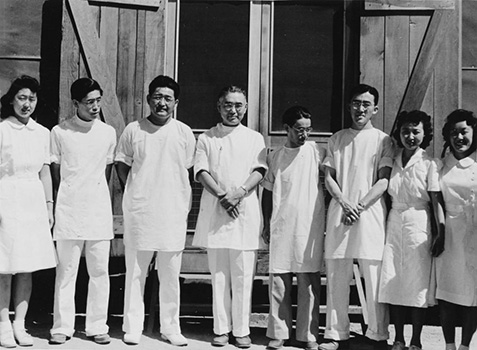

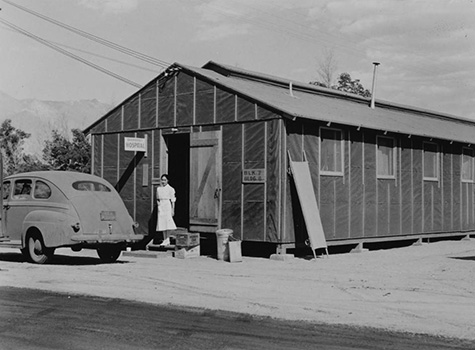

Report on Health and Physical Education at Manzanar - June 1944

|

|

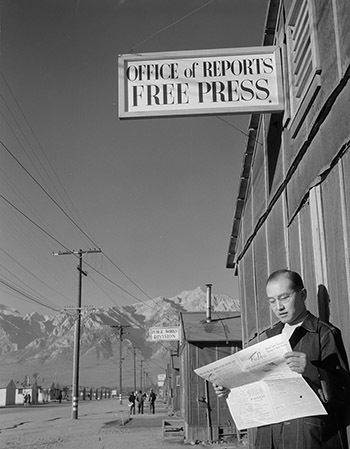

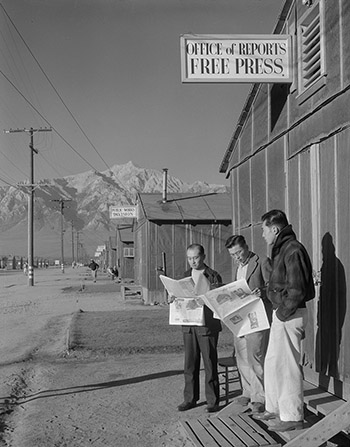

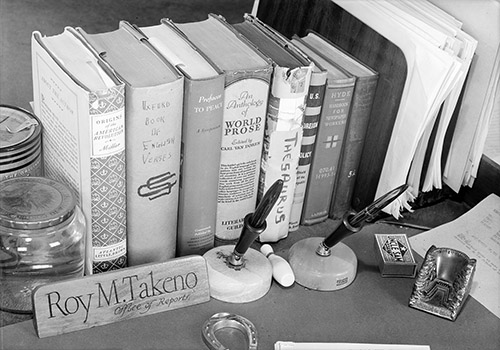

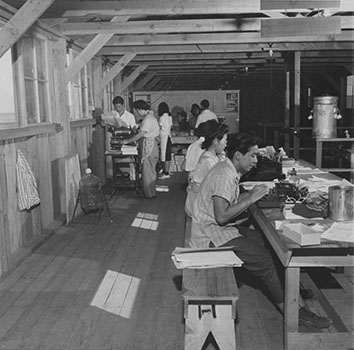

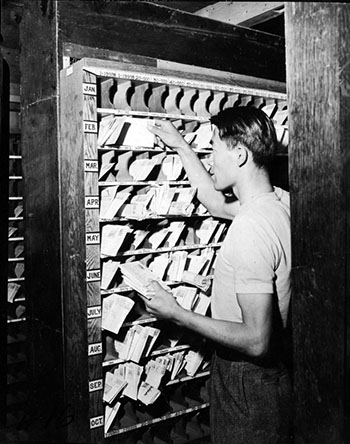

Journalism

Manzanar Free Press Anniversary Edition - March 20, 1943

|

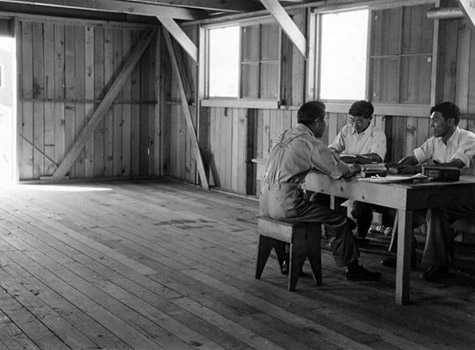

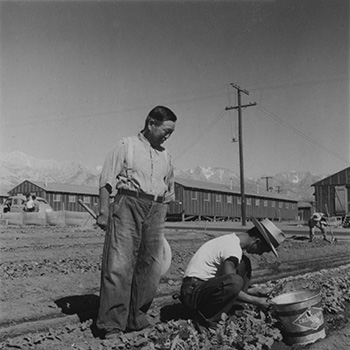

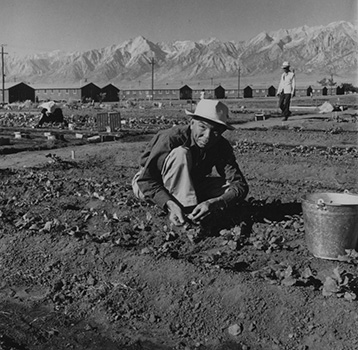

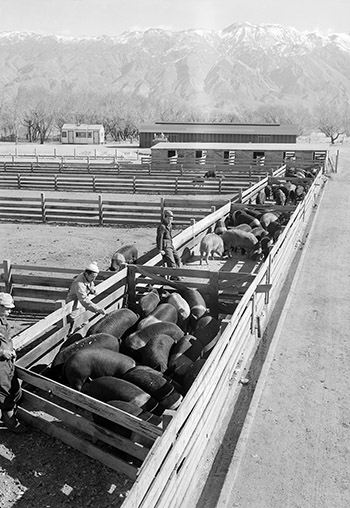

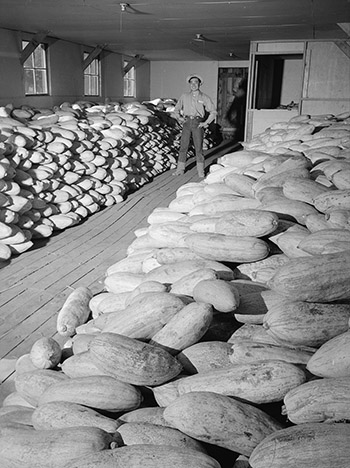

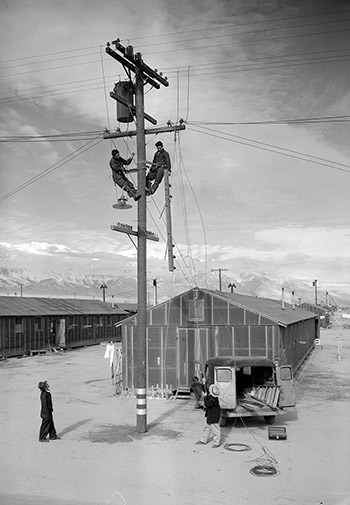

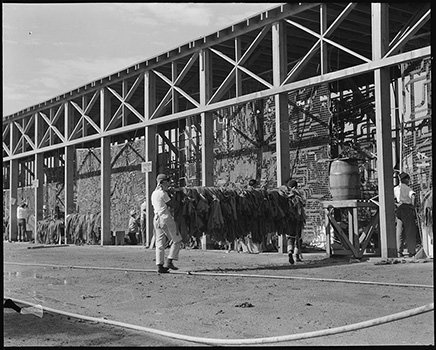

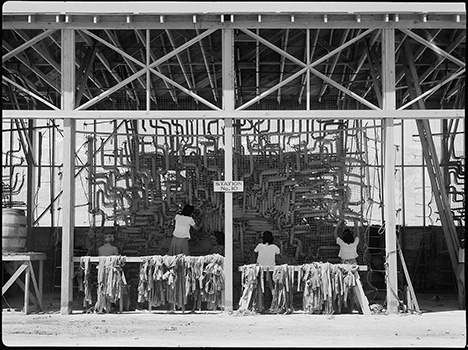

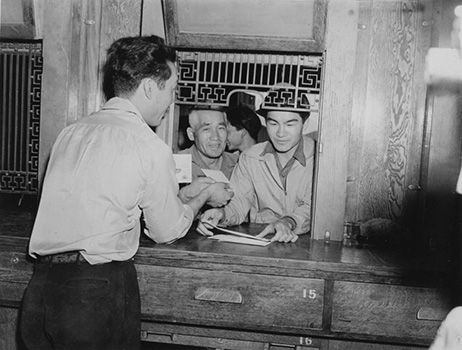

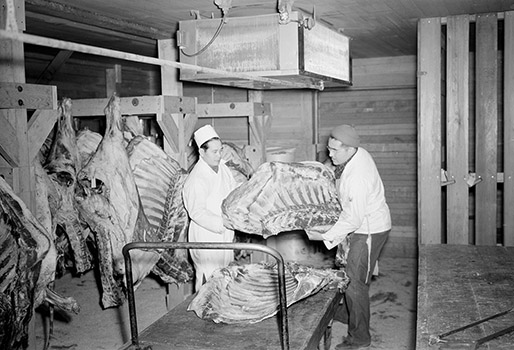

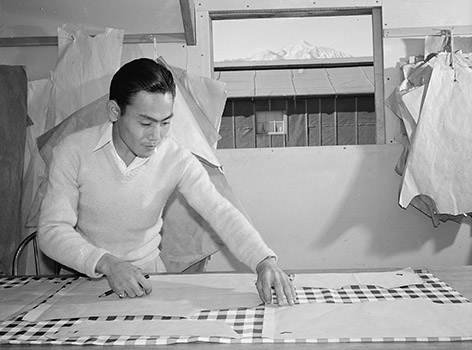

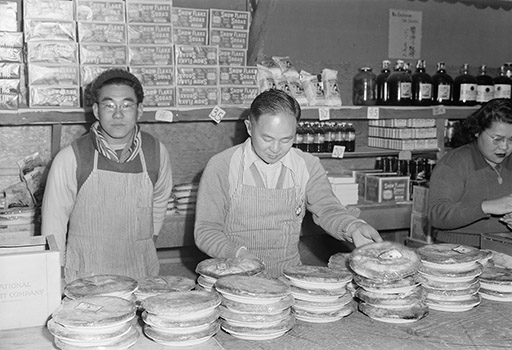

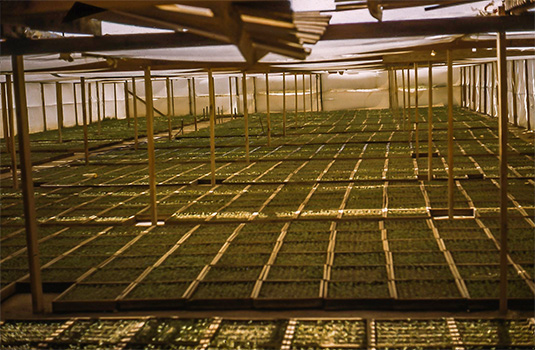

Agriculture & Other Work / Social Activities

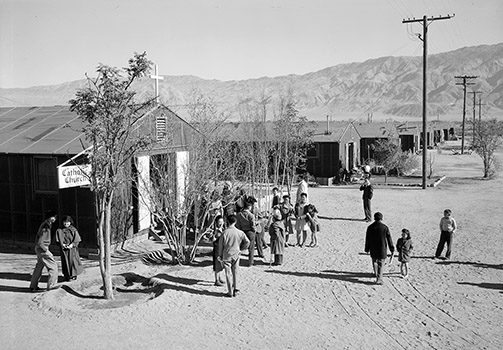

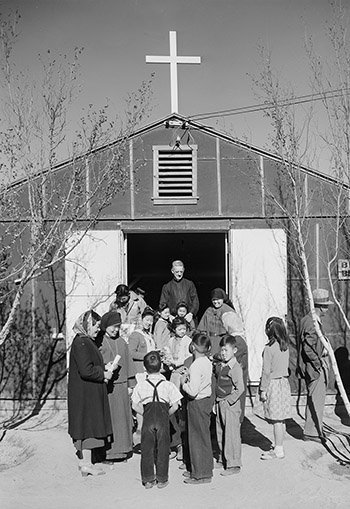

Religious Services

Catholic Church (Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress) (Photographer Ansel Adams)

|

Epilogue (excerpts from Farewell to Manzanar) "As I came to understand what Manzanar had meant, it gradually filled me with shame for being a person guilty of something enormous enough to deserve that kind of treatment. In order to please my accusers, I tried, for the first few years after our release, to become someone acceptable. I both succeeded and failed. By the age of seventeen I knew that making it, in the terms I had tried to adopt, was not only unlikely, but false and empty, no more authentic for me than trying to emulate my Great-aunt Toyo. I needed some grounding of my own, such as Woody had found when he went to commune with her and with our ancestors in Ka-ke. It took me another twenty years to accumulate the confidence to deal with what the equivalent experience would have to be for me. It's outside the scope of this book to recount all that happened in the interim. Suffice to say, I was the first to marry out of my race. As my husband and I began to raise our family, and as I sought for ways to live agreeably in Anglo-American society, my memories of Manzanar, for many years, lived far below the surface. When we finally started to talk about making a trip to visit the ruins of the camp, something would inevitably get in the way of our plans. Mainly my own doubts, my fears. I half-suspected that the place did not exist. So few people I met in those years had even heard of it, and those who had knew so little about it, sometimes I imagined I had made the whole thing up, dreamed it. Even among my brothers and sisters, we seldom discussed the internment. If we spoke of it all all, we joked. When I think of how that secret lived in all our lives, I remember the way Kiyo and I responded to a little incident soon after we got out of camp. We were sitting on a bus-stop bench in Long Beach, when an old, embittered woman stopped and said, 'Why don't all you dirty Japs go back to Japan!' She spit at us and passed on. We said nothing at the time. After she stalked off down the sidewalk we did not look at each other. We sat there for maybe fifteen minutes with downcast eyes and finally got up and walked home. We couldn't bear to mention it to anyone in the family. And over the years we never spoke of this insult. It stayed alive in our separate memories, but it was too painful to call out into the open. .............................................. We were alone out there [Jeanne & her family finally made it to Manzanar.], too far from the road to hear anything but wind. I thought of Mama, now seven years gone. For a long time I stood gazing at the monument [The Japanese 'Memorial to the Dead']. I couldn't step inside the fence. I believe in ghosts and spirits. I knew I was in the presence of those who had died at Manzanar. I also felt the spiritual presence that always lingers near awesome wonders like Mount Whitney. Then, as if rising from the ground around us on the valley floor, I began to hear the first whispers, nearly inaudible, from all those thousands who once had lived out here, a wide, windy sound of the ghost of that life. As we began to walk, it grew to a murmur, a thin steady hum. ................................................ My husband started walking them [her children] back to the car. I stayed behind a moment longer, first watching our eleven-year-old stride ahead, leading her brother and sister. She has long dark hair like mine and was then the same age I had been when the camp closed. It was so simple, watching her, to see why everything that had happened to me since we left camp referred back to it, in one way or another. At that age your body is changing, your imagination is galloping, your mind is in that zone between a child's vision and an adult's. Papa's life ended at Manzanar, though he lived for twelve more years after getting out. Until this trip I had not been able to admit that my own life really began there. The times I thought I had dreamed it were one way of getting rid of it, part of wanting to lose it, part of what you might call a whole Manzanar mentality I had lived with for twenty-five years. Much more than a remembered place, it had become a state of mind. Now, having seen it, I no longer wanted to lose it or to have those years erased. Having found it, I could say what you can only say when you've truly come to know a place: Farewell." (JWH) |

Sign Guestbook View Old Guest Book Entries Oct 1999 - Feb 2015 (MS Word) |

CONTACT the Pigmy Packer |

View Guestbook View Old Guest Book Entries Oct 1999 - Feb 2015 (PDF) |